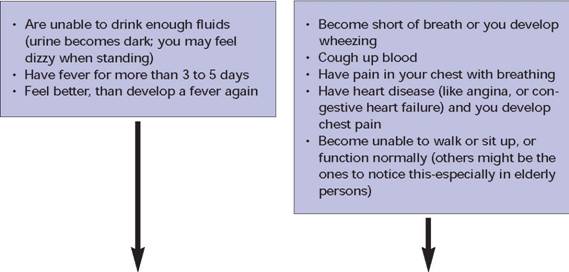

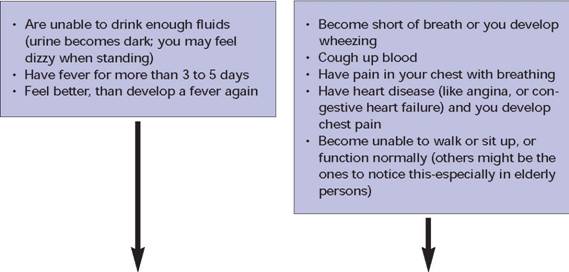

But IF you

Or IF you

Or IF you

CALL your healthcare provider GO RIGHT AWAY for healthcare

“To assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women; by authorizing enforcement of the standards developed under the Act; by assisting and encouraging the States in their efforts to assure safe and healthful working conditions; by providing for research, information, education, and training in the field of occupational safety and health.”

This publication provides a general overview of a particular standards-related topic. This publication does not alter or determine compliance responsibilities which are set forth in OSHA standards, and the Occupational Safety and Health Act. Moreover, because interpretations and enforcement policy may change over time, for additional guidance on OSHA compliance requirements, the reader should consult current administrative interpretations and decisions by the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission and the courts.

Material contained in this publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced, fully or partially, without permission. Source credit is requested but not required.

This information will be made available to sensory impaired individuals upon request. Voice phone: (202) 693-1999; teletypewriter (TTY) number: 1-877-889-5627.

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

|---|---|

| EPA | U.S. Environmental Protection Agency |

| HEPA | high-efficiency particulate air |

| HHS | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services |

| JCAHO | Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations |

| LRN | Laboratory Response Network |

| NIOSH | National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health |

| OSH Act | Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 |

| OSHA | Occupational Safety and Health Administration |

| PAPR | powered air-purifying respirator |

| PLHCP | physician or another licensed healthcare professional |

| PPE | personal protective equipment |

| RT-PCR | reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction |

| SARS | severe acute respiratory syndrome |

| SNS | Strategic National Stockpile |

| SPN | Sentinel Provider Network |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| Particulate Respirator Filter Type | Percentage (%) of 0.3 µm airborne particles filtered out | Not resistant to oil | Somewhat resistant to oil | Strongly resistant to oil (oilproof) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N95 | 95 | X | ||

| N99 | 99 | X | ||

| N100 | 99.97 | X | ||

| R95 | 95 | X | ||

| R99 | 99 | X | ||

| R100 | 99.97 | X | ||

| P95 | 95 | X | ||

| P99 | 99 | X | ||

| P100 | 99.97 | X |

| General Pandemic Planning Resources | ||

|---|---|---|

| Department of Health and Human Services | http://www.pandemicflu.gov | Federal/State pandemic disaster planning resources; updated as new information becomes available. |

| Department of Health and Human Services | http://www.pandemicflu.gov/plan/tab6.html | Checklists for specific healthcare services, hospitals, clinics, home health, long-term care, EMS. |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | http://www2a.cdc.gov/od/fluaid | The FluAid program is a resource for state and local planners to estimate range of deaths, hospitalizations, and outpatient visits for a community. |

| http://www.cdc.gov/flu/flusurge.htm | The FluSurge program estimates the impact of a pandemic on the surge capacity of individual healthcare facilities, (i.e., hospital beds, ventilators). | |

| Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality | Multiple resources on disaster planning including surge capacity, stockpiles, and developing alternate care sites: | |

| http://www.ahrq.gov/browse/bioterbr.htm | AHRQ disaster planning website | |

| http://www.ahrq.gov/research/havbed/ | Issues addressing bed capacity | |

| http://www.ahrq.gov/research/shuttered/shuttools.pdf | Opening shuttered hospitals to address surge capacity | |

| http://www.ahrq.gov/news/ulp/btbriefs/btbrief3.htm | Conferences to optimize surge capacity | |

| http://www.ahrq.gov/research/devmodels/ | Development of models for emergency preparedness | |

| http://www.ahrq.gov/research/epri/ | Emergency preparedness resource inventory | |

| http://www.ahrq.gov/research/altstand/ | Altered standards of care in mass casualty event | |

| http://www.ahrq.gov/research/altsites.htm | Alternate site use during an emergency | |

| http://www.ahrq.gov/research/biomodel.htm | Computer staffing model | |

| http://www.ahrq.gov/research/health/ | Integrating with public health agencies | |

| http://www.ahrq.gov/research/biomodel3/toc.asp#top | Bioterrorism and Epidemic Response Model | |

| Department of Veterans Affairs | http://www.publichealth.va.gov/flu/pandemicflu.htm | The VA has information on infection control and other pandemic resources. |

| World Health Organization | http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/ influenza/WHO_CDS_CSR_GIP_2005_5/en/index.html | International planning strategies and global pandemic information |

| http://www.who.int/csr/en/ | ||

| Food and Drug Administration | http://www.fda.gov/oc/opacom/hottopics/flu.html | Information on vaccine, antiviral medication, fraud investigations. |

| Resources for Coordination with State and Local Agencies | ||

| Association of State and Territorial Health Officials | http://www.astho.org/ | Resources for pandemic planning, including state health department listings and state pandemic plans. |

| California | http://www.heics.com/ | Hospital Emergency Incident Command System (HEICS), an example of an emergency management plan for healthcare facilities. |

| Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations | http://www.jointcommission.org/PublicPolicy/ep_guide.htm | Resources for integrations with community disaster planning. Surge hospital planning and implementation. |

| http://www.jointcommission.org/PublicPolicy/surge_hospitals.htm | ||

| Resources for Medications and Vaccination Information and Planning | ||

| Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality | http://www.ahrq.gov/research/biomodel3/ | Part of the Weil/Cornell Bioterrorism and Epidemic Response Module (BERM), specifically addressing planning for mass prophylaxis. |

| Department of Health and Human Services | http://www.pandemicflu.gov/vaccine | Up-to-date information on vaccines, medication and tests for pandemic influenza. |

| Disaster and Pandemic Influenza Tabletop Exercises and Drills | ||

| Department of Health and Human Services | http://www.hhs.gov/nvpo/pandemics/tabletopex.html | Tools to assist planning and conducting tabletop exercises for pandemic influenza planning. |

| Hand cleaning | Gloves | Gowns | Eye protection | Respiratory protection | Room | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airborne Infection Isolation + Contact | •Between patients

•Immediately after glove removal •Whenever hands may be contaminated by secretions or body fluids •Use an alcohol-based hand rub or wash with antimicrobial soap and water |

•When caring for patients

•When touching areas or handling items contaminated by patients |

•With patient contact

|

•When within 3 feet of patient

•With aerosol-generating procedures |

•Use fit-tested N95 mask OR positive air purifying respirator (PAPR) or fit-tested elastomeric respirator

Patients • Wear masks during transport. •Use masks with elastic straps; avoid masks that tie on. |

•Negative airflow private room when possible

•Air exhausted outdoors or through high-efficiency filtration. •Door kept closed. |

| Hand cleaning | Gloves | Gowns | Eye protection | Respiratory protection | Room | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Droplet | •Between patients

•Immediately after glove removal •Whenever hands may be contaminated by secretions or body fluids •Use an alcohol-based hand rub or wash with antimicrobial soap and water |

•When caring for patients

•When touching areas or handling items contaminated by patients |

•Not required

|

•With aerosol-generating procedures

|

•Wear surgical or procedure-type masks in patient rooms or when within 3 feet of patients; change when moist

•Wear fit-tested N95 respirator or equivalent with aerosol generating procedures Patients •Wear masks during transport. •Use masks with elastic straps; avoid masks that tie on. |

•Private room when possible

•Door may be open. |

| Who Can Act? | What Public Health Measures? | Why? |

|---|---|---|

| Individuals | Cleaning hands regularly. | Reduces transfer of microorganisms from the hands to the eyes, nose, or mouth. Reduces transmission of microorganisms carried on hands from person to person. |

| Following respiratory hygiene rules (covering the mouth and nose with tissues when coughing or sneezing). | Prevents dispersal of respiratory viruses in the air. | |

| Getting seasonal influenza vaccinations. | Prevents individuals from getting/transmitting seasonal influenza, which reduces burden on health care system, and keeps the individual well and able to conduct daily business. Reduces likelihood of genetic reassortment of influenza strains when a person is infected with more than one strain. Helps people become accustomed to getting vaccinations. | |

| Avoiding contact with sick persons-staying at least three to five feet away. | Reduces likelihood of one's getting and transmitting influenza. | |

| Staying home when sick- from work, school, public places. | Reduces transmission of influenza to other persons. | |

| Wearing masks when sick with influenza, if able to tolerate. | Reduces transmission to others. | |

| Health care providers | Tracing contacts. | Locates and allows potentially exposed persons to be informed and able to take measures to avoid exposing others. |

| Isolating people with suspected or confirmed influenza. | Reduces transmission of influenza to others. | |

| Quarantining people exposed to influenza. | Reduces transmission of influenza to other persons. Because the incubation period of influenza is about 2 days, quarantine time would also be short (actual time will be determined by the characteristics of the pandemic influenza virus). | |

| Wearing personal protective equipment - masks or respirators, gowns, gloves, goggles. | Reduces risk of getting influenza and potential of transmitting it to others. | |

| Business, community, regional, and national organizations and leaders | Developing, manufacturing, stockpiling, and distributing antiviral medications. | Treats influenza or prevents its spread. |

| Developing, manufacturing, stockpiling, and distributing vaccine. | Prevents influenza. | |

| Reducing non-essential travel. | Reduces the number of persons an individual has contact with and slows the spread of influenza from region to region. | |

| Closing schools. | Children usually have many more close contacts than adults; closing schools greatly reduces transmission of influenza within schools, within families, and within communities. | |

| Declaring "snow days" (temporarily closing businesses, offices), postponing public gatherings. | Reduces contacts among persons; has potential to reduce transmission. | |

| Enabling employees to work from home; making teleworking/telecommuting possible. | Reduces contacts among persons; has potential to reduce transmission. | |

| Partitioning space. | Limiting access to a building or facility by screening those who enter for fever, respiratory symptoms, and possible recent exposure. |

| What type of transmission is confirmed? | Where are the cases? | Are there cases at DHMC? | Alert Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| None or sporadic cases only | Anywhere in the world | No | Ready |

| Person-to-person transmission | Anywhere outside the U.S. and bordering countries (Canada, Mexico) | No | Green |

| Person-to-person transmission | In the U.S., Canada or Mexico | No | Yellow |

| Person-to-person transmission | In region: NH/VT or close to borders | Does not matter | Orange |

| Does not matter | At DHMC or DC | Yes, but no nosocomial transmission | "Controlled Orange" |

| Person-to-person transmission | At DHMC or DC | Yes, with nosocomial transmission, from known sources only | Orange |

| Person-to-person transmission | At DHMC or DC | Yes, with nosocomial transmission, sources not clear | Red |

Or IF you

Or IF you

| Date | Time | Observations* | Temperature | Medication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure | Influenza Types Detected | Acceptable Specimens | Time for Results | Rapid result available |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viral culture | A and B | NP swab (2), throat swab, nasal wash, bronchial wash, nasal aspirate, sputum | 3-10 days (3) | No |

| Immunofluorescence DFA Antibody Staining | A and B | NP swab (2), nasal wash, bronchial wash, nasal aspirate, sputum | 2-4 hours | No |

| RT-PCR5 | A and B | NP swab (2), throat swab, nasal wash, bronchial wash, nasal aspirate, sputum | 2-4 hours | No |

| Serology | A and B | paired acute and convalescent serum samples (6) | >2 weeks | No |

| Enzyme Immuno Assay (EIA) | A and B | NP swab (2), throat swab, nasal wash, bronchial wash | 2 hours | No |

| Rapid Diagnostic Tests | ||||

| Directigen Flu A (7) (Becton-Dickinson) | A | NP wash and aspirate | <30 minutes | Yes |

| Directigen Flu A+B (7,9) (Becton-Dickinson) | A and B | NP swab (2), aspirate, wash; lower nasal swab; throat swab; bronchioalveolar lavage | <30 minutes | Yes |

| Directigen EZ Flu A+B (7,9) (Becton-Dickinson) | A and B | NP swab (2), aspirate, wash; lower nasal swab; throat swab; bronchioalveolar lavage | <30 minutes | Yes |

| FLU OIA4,7 (Biostar) | A and B | NP swab (2), throat swab, nasal aspirate, sputum | <30 minutes | Yes |

| FLU OIA A/B (7,9) (Biostar) | A and B | NP swab (2), throat swab, nasal aspirate, sputum | <30 minutes | Yes |

| XPECT Flu A&B (7,9) (Remel) | A and B | Nasal wash, NP swab (2), throat swab | <30 minutes | Yes |

| NOW Influenza A (8,9) (Binax) | A | Nasal wash/aspirate, NP swab (2) | <30 minutes | Yes |

| NOW Influenza B (8,9) (Binax) | B | Nasal wash/aspirate, NP swab (2) | <30 minutes | Yes |

| NOW Influenza A&B (8,9) (Binax) | A and B | Nasal wash/aspirate, NP swab (2) | <30 minutes | Yes |

| OSOM® Influenza A&B (9) (Genzyme) | A and B | Nasal swab | <30 minutes | Yes |

| QuickVue Influenza Test (4,8) (Quidel) | A and B | NP swab (2), nasal wash, nasal aspirate | <30 minutes | Yes |

| QuickVue Influenza A+B Test (8,9) (Quidel) | A and B | NP swab (2), nasal wash, nasal aspirate | <30 minutes | Yes |

| SAS Influenza A Test (7,8,9) | A | NP wash2, NP aspirate (2) | <30 minutes | Yes |

| SAS Influenza B Test (7,8,9) | B | NP wash2, NP aspirate (2) | <30 minutes | Yes |

| ZstatFlu (4,8) (ZymeTx) | A and B | throat swab | <30 minutes | Yes |

| Region I (CT,* ME, MA, NH, RI, VT*) JFK Federal Building, Room E340 Boston, MA 02203 (617) 565-9860 |

Region VI (AR, LA, NM,* OK, TX) 525 Griffin Street, Room 602 Dallas, TX 75202 (972) 850-4145 |

| Region II (NJ,* NY,* PR,* VI*) 201 Varick Street, Room 670 New York, NY 10014 (212) 337-2378 |

Region VII (IA,* KS, MO, NE) City Center Square 1100 Main Street, Suite 800 Kansas City, MO 64105 (816) 426-5861 |

| Region III (DE, DC, MD,* PA, VA,* WV) The Curtis Center 170 S. Independence Mall West Suite 740 West Philadelphia, PA 19106-3309 (215) 861-4900 |

Region VIII (CO, MT, ND, SD, UT,* WY*) 1999 Broadway, Suite 1690 PO Box 46550 Denver, CO 80202-5716 (720) 264-6550 |

| Region IV (AL, FL, GA, KY,* MS, NC,* SC,* TN*) 61 Forsyth Street, SW Atlanta, GA 30303 (404) 562-2300 |

Region IX (American Samoa, AZ,* CA,* HI,* NV,* Northern Mariana Islands) 90 7th Street, Suite 18-100 San Francisco, CA 94103 (415) 625-2547 |

| Region V (IL, IN,* MI,* MN,* OH, WI) 230 South Dearborn Street Room 3244 Chicago, IL 60604 (312) 353-2220 |

Region X (AK,* ID, OR,* WA*) 1111 Third Avenue, Suite 715 Seattle, WA 98101-3212 (206) 553-5930 |